Biofabrics are materials that are created through synthetic proccesses based upon sustainable and renewable plant resources, similarily to biotextiles, which are textiles designed for use in a medical environment (artificial hearts, arteries, skin, etc). The emerging field of biofabrics is being pioneered by the designer Suzanne Lee. She started off by growing fabrics from kombucha,a fermented tea, and is now working with Modern Meadow, leading their initiative to grow leather (Modern Meadow is currently working on growing beef from bovine cells). Though this project is young, they have already been able to successfully grow leather in petri dishes and scientists at Modern Meadow have also been able to manipulate cell cultures to alter the material's strength, texture, weight, and elasticity. Suzanne explains that with this technology, they can create "leather that is as lightweight and transparent as a butterfly wing" or leather with "the natural stretch of rubber" or even a material that's as responsive as "chameleon skin". She sees a future where your clothes can sustain themselves off of your dead cells to clean and repair itself or clothes that could react to your body temperature and rearrange themselves for maximum comfort, like how feathers and fur might fluff up to act as insulators. Currently, there are several startupts pursuing this new field, such as Bolt Threads, who has been able to bioengineer a material similar to spider silk; these new techonologies could enable us to mass produce materials that are usually rare, expensive or unsustainable.

Her early ventures into microbiology and biofabrics were introduced to her by a biologist, who suggested that microorganisms and bacteria, not just cotton, could also produce cellulose, one of the most common fibers in the world. Suzanne grew kombucha and as she fed the bacteria sugar they would spin a "nano-scale mesh" of cellulose. This material would then dry up into a leather-like material. It readily absorbs plant dyes, is stronger than dozens of fabrics and when draped across a dress form when wet, would knit itself together, which completely eliminates the manafacturing and production.

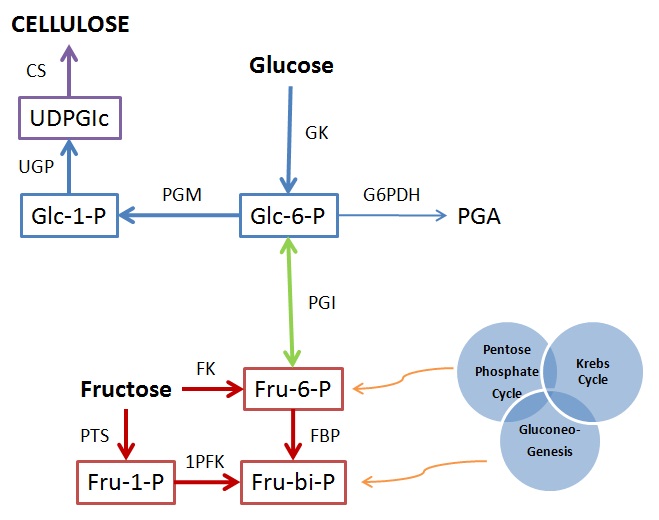

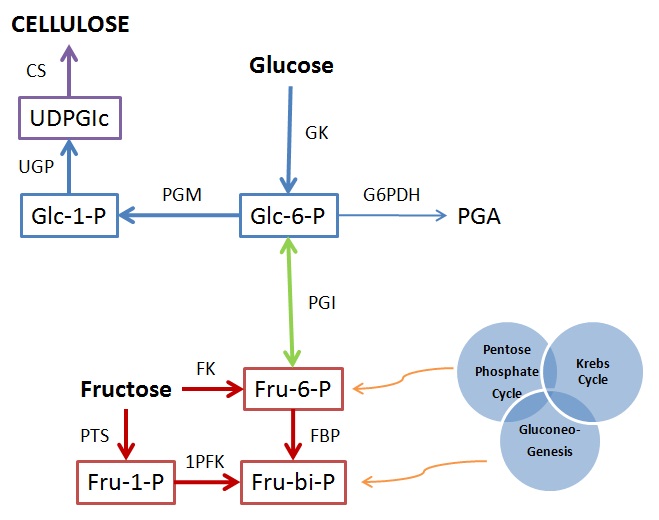

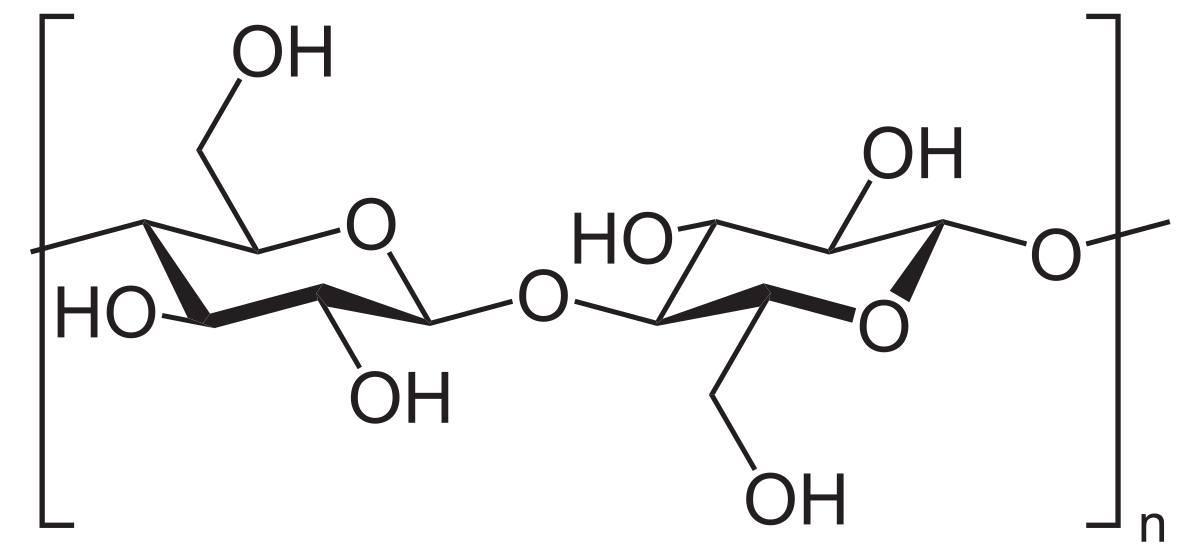

This bacterial nanocellulose is similar to the fiber of cotton (90% cellulose); they are both made of cellulose, which is a polysaccaride composed of a linear chain of glucose units, which when broken down to the molecular level, is made up of oxygen and hydroxide. The main difference is that the nanocellulose has a much more compact composition, its nanofibrils making it several times more durable, and stronger than the fibers of cotton; the share similar molecular qualities, but have different macromolecular qualities that make bacterial nanocellulose the better of the two. The production of bacterial nanocellulose is produced from the two part process of synthesis of uridine diphosphuglucose, a nucleotide sugar, and the polymerization of glucose. The production of cellulose is dependent on: growth medium, environmental conditions, and the formation of byproducts. The medium in which the fermentation is occurring, must contain: carbon, nitrogen, and other macro and micro nutrients that are necessary for bacterial growth. Bacteria grow best in conditions when supplied with an abundance of carbon and minimum nitrogen sources. The most common sources of carbon for cellulose proudction are glucose and sucrose, sugars; maltose, fructose, xylose, starch and glycerol have been tried, to varying degrees of success. Experimenting with varius other ingredients have also been shown to boost production of cellulose, such as acetic acid, while precursor molecules such as amino acids and methionine improve production as well, acting like a catalyst in the reaction, by providing alternate metabolic pathways for the reaction.

So why should we pursue, or even consider, Suzanne Lee's vision? The fashion world is being swept by an eco-fashion movement that focuses on sustainability and social responsibility; keeping human impact upon the environment at a minimum. The fashion industry is composed of a complex supply chains of production: raw materials, textile manafacturing, clothing construction, garment dyeing, shipping, retail, and eventually, use and disposal. A plain cotton t shirt or jeans takes about 5,000 gallons of water to make, and dyes take up even more water. Cotton is also one of the thirstiest plants, while being one of the most fragile: while it accounts for only 2.4% of the world's cropland, it consumes 10% of all agricultural chemicals and 25% of insecticides. Aside from the half a trillion water consumption the current cotton crop needs anually, the chemicals and dyes used to treat the cotton afterwards are usually released into ecosystem. The impacts of the industries that support fast fashion are unsustainable and the proof is in the countries that have participated; Uzkeistan was formerly one of the largest exporter of cotton, until it caught up with them. Their ecosystem is now a wasteland: the land and sea are all barren, too filled with toxins to support any life, and the lack of water has also made the weather harsher. In Indonesia, the toxicity of the Citarum River is high enough to burn human skin on contact; all resulting from the purposeful, careless disposal of dyes and chemicals. With the biochemical advancements in the mass farming of bacterial nanocellulose, many of these issues can be eliminated. Biochemists hope that they can genetically engineer bacteria and algae to be fully functional to produce nanocellulose in mass quantities.

Sources:

This bacterial nanocellulose is similar to the fiber of cotton (90% cellulose); they are both made of cellulose, which is a polysaccaride composed of a linear chain of glucose units, which when broken down to the molecular level, is made up of oxygen and hydroxide. The main difference is that the nanocellulose has a much more compact composition, its nanofibrils making it several times more durable, and stronger than the fibers of cotton; the share similar molecular qualities, but have different macromolecular qualities that make bacterial nanocellulose the better of the two. The production of bacterial nanocellulose is produced from the two part process of synthesis of uridine diphosphuglucose, a nucleotide sugar, and the polymerization of glucose. The production of cellulose is dependent on: growth medium, environmental conditions, and the formation of byproducts. The medium in which the fermentation is occurring, must contain: carbon, nitrogen, and other macro and micro nutrients that are necessary for bacterial growth. Bacteria grow best in conditions when supplied with an abundance of carbon and minimum nitrogen sources. The most common sources of carbon for cellulose proudction are glucose and sucrose, sugars; maltose, fructose, xylose, starch and glycerol have been tried, to varying degrees of success. Experimenting with varius other ingredients have also been shown to boost production of cellulose, such as acetic acid, while precursor molecules such as amino acids and methionine improve production as well, acting like a catalyst in the reaction, by providing alternate metabolic pathways for the reaction.

So why should we pursue, or even consider, Suzanne Lee's vision? The fashion world is being swept by an eco-fashion movement that focuses on sustainability and social responsibility; keeping human impact upon the environment at a minimum. The fashion industry is composed of a complex supply chains of production: raw materials, textile manafacturing, clothing construction, garment dyeing, shipping, retail, and eventually, use and disposal. A plain cotton t shirt or jeans takes about 5,000 gallons of water to make, and dyes take up even more water. Cotton is also one of the thirstiest plants, while being one of the most fragile: while it accounts for only 2.4% of the world's cropland, it consumes 10% of all agricultural chemicals and 25% of insecticides. Aside from the half a trillion water consumption the current cotton crop needs anually, the chemicals and dyes used to treat the cotton afterwards are usually released into ecosystem. The impacts of the industries that support fast fashion are unsustainable and the proof is in the countries that have participated; Uzkeistan was formerly one of the largest exporter of cotton, until it caught up with them. Their ecosystem is now a wasteland: the land and sea are all barren, too filled with toxins to support any life, and the lack of water has also made the weather harsher. In Indonesia, the toxicity of the Citarum River is high enough to burn human skin on contact; all resulting from the purposeful, careless disposal of dyes and chemicals. With the biochemical advancements in the mass farming of bacterial nanocellulose, many of these issues can be eliminated. Biochemists hope that they can genetically engineer bacteria and algae to be fully functional to produce nanocellulose in mass quantities.

Sources:

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cellulose

- http://www.popsci.com/meet-woman-who-wants-growing-clothing-lab

- http://www.ecouterre.com/grow-your-own-microbial-leather-in-your-kitchen-diy-tutorial/biocouture-suzanne-lee-4/

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polysaccharide

- http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00253-015-7243-4

This is awesome! Even if the idea of my clothes using my dead skin cells as sustenance is kinda creepy, the idea behind it is incredible. The way that biofabrics are portrayed in this post definitely shine a favorable light upon them. However, one discrepancy in your post that might lead to further hindrances in making this kind of material a commonality is how long it takes the bacteria to make this leather-type material. If generation times are long, then this process will see a hard time making it to market until it's improved. So, how long does it take to make these kinds of materials with the bacterial process?

ReplyDeleteI know it takes about a month to grow a 7x6 piece in 4 weeks. Basically, just get a larger container and add more ingredients and itll form to the size of the container within two weeks and be about 2cm thick.

Delete